If you've missed it,

Glen Fuller has been so kind as to tell me not to continue writing posts on OOO and Deleuze. He has also,

through his pedagogical discourse, explained to me that I can't just "use" Deleuze and Guattari, but that in fact I have to know every thing about them, know all of the secondary literature, and read all of the philosophers D&G use themselves. So,this post is an extremely lengthy response to Glen's comments to say thanks for all of the helpful information on how to use “concepts.” Let's begin:

So let me see if I got this right. First I need to understand the development of the original concept. Okay, fair enough. According to Ian Buchannan’s

Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus:

In the various interviews they gave following the publication of Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze invariably says that their starting point was the concept of the desiring-machine, the invention of which he attributes to Guattari. There is no record of how Guattari came up with the idea, but on the evidence of his recently published notebooks, The Anti-Oedipus Papers, his clinical experience at La Borde had a large part to play. As Deleuze tells it, Guattari came to him with an idea for a productive unconscious, built around the concept of desiring-machines. In its first formulation, though, it was judged by them both to be too structuralist to achieve the kind of radical breakthrough in understanding how desire functions that they were both looking for in their own ways. At the time, according to Deleuze, he was working - 'rather timidly' in his own estimation - 'solely with concepts' and could see that Guattari's ideas were a step beyond where his thinking had reached (N, 13/24). Unsurprisingly, Guattari's version of events concurs with Deleuze's, though he credits the latter with being the one whose thinking had advanced the furthest. Guattari describes himself as wanting to work with Deleuze both to make his break with Lacanian formulations more thoroughgoing and to give greater system and order to his ideas. But as we've already seen their collaboration was also always more than a simple exchange of ideas, each providing the other with something they lacked. They were both looking for a discourse that was both political and psychiatric but didn't reduce one dimension to the other. Neither seemed to think he could discover it on his own (N, 13/24). To put it another way, we could say that Deleuze and Guattari were both of the view that a mode of analysis that insists on filtering everything through the triangulating lens of daddy-mommy-me could not hope to explain either why or how May '68 happened, nor indeed why it went they way it did. The students at the barricades may have been rebelling against the 'paternal' authority of the state, but they were also rebelling against the very idea of the state and the former does not explain the latter. (emphasis added 38-39)

So, in essence the development of the desiring-machine was centered on the need to develop a concept that did two things: 1) described desire counter to the Freudian Oedipal complex which reduced every desire to a sexual desire (daddy-mommy-me) but could still be used to describe both the political and psychiatric, and 2) explained how desire was ultimately productive.

This makes perfect sense then when in Anti-Oedipus our two authors argue the following:

It is often thought that Oedipus is an easy subject to deal with, something perfectly obvious, a “given” that is there from the very beginning. But that is not all: Oedipus presupposes a fantastic repression of desiring machines. And why are they repressed? To what end? Is it really necessary or desirable to submit to such a repression? And what means are to be used to accomplish this? What ought to go inside the Oedipus triangle, what sort of thing is required to construct it? Are a bicycle horn and my mother’s arse sufficient to do the job? Aren’t there more important questions than these, however? Given a certain effect, what machine is capable of producing it? And given a certain machine, what can it be used for? Can we possibly guess, for instance, what a knife rest is used for if all we are given is a geometrical description of it? (3)

D&G find their answer to these questions in the desiring-machine and the schizophrenic. For the schizophrenic experiences the nature of the world differently. Nature is a process of production. And D&G mean three things by the word process: 1) as “incorporating recording and consumption within production itself, thus making the productions of one and the same process,” and 2) “man and nature are not like two opposite terms confronting each other – not even in the sense of bipolar opposites within a relationship of causation, ideation or expression (cause and effect, subject and object, etc.); rather they are one and the same essential reality, the producer product,” and 3) process “must not be viewed as a goal or an end in itself, nor must it be confused with an infinite perpetuation of itself” (4-5).

Desiring-machines work in binary (that is, always coupled with another machine) to produce such a process: “[T]here is always a flow-producing machine, and another machine connected to it that interrupts or draws off part of this flow (the breast-the mouth). And because the first machine is in turn connected to another whose flow it interrupts or partially drains off, the binary series is linear in every direction” (5). What this means is that every machine must always be connected to another machine and at every connection there is a new machine. For, “a connection with another machine is always established, along a transverse path, so that one machine is always established, along a transverse path, so that one machine always interrupts the current of the other or ‘sees’ its own current interrupted” (6). And it is in this coupling from flow-machine to interrupting-machine, and so on, that D&G argue that producing is always “grafted” onto production. But what this also means is that every desiring-machine should also be seen as a product of production.

However, one of the products of a desiring-machine (since it holds to the process described above) is its body without organs (BwO). D&G state that “[t]he body without organs is nonproductive; nonetheless it is produced, at a certain place and a certain time in the connective synthesis, as the identity producing and the product...” (8). The BwO is a wild collection of unactualized forces, or a blank space across which desiring-machines constantly cut across, “so that the desiring-machines seem to emanate from it in the apparent objective movement that establishes a relationship between the machines and the body without organs” (11). So that desiring-machines constantly create the organism and its opposite – the BwO.

So it is with these concepts (the BwO and the desiring-machine) that D&G are able to form a schizoanalysis that describes a non-Freudian-psychoanalytic sense of desire that is in itself a producing/product. For, as they note, once this is done and “desire is productive, it can be productive only in the real world and can produce only reality…The real is the end product, the result of the passive syntheses of desire as autoproduction of the unconscious. Desire does not lack anything; it does not lack its object. It is, rather, the subject that is missing in desire, or desire that lacks a fixed subject; there is no fixed subject unless there is repression. Desire and its object are one and the same thing: the machine, as a machine of a machine” (26).

So, now that I’ve explored the creation and problematic of D&G’s desiring-machine, let’s look at the problematic of OOO.

OOO was created in response to a certain version of realism in which the things in the world (including the world itself) were all a product of the human mind. Given its name by Quentin Meillassoux in After Finitude, this type of realism became known by the name of Correlationism – pointing to the necessary correlation of human thinking and world. Contrary to correlationsim, OOO proposed a weird realism in which all objects enjoyed the same ontological status as all other objects. As Ian Bogost once put it (and I’m paraphrasing here) OOO does not claim that all things are equal, but that all things equally are. The important thing to note is that like D&G, OOO was attempting to understand the world counter to an overwhelming philosophical world-view. We could say that for OOO objects do two things: 1) describes reality counter to the correlationist view which reduces the world to human thoughts and 2) explains how objects are ultimately productive.

For D&G it was Freud’s Oedipal complex by which everything seemed to be interrupted, and for OOO it was correlationism by which everything became a product of the human mind. OOO found its savior in the creation of objects – everything is considered an object (including its opposite, the subject). Now, I’m not going to go into Graham Harman’s objects (as I’m really still waiting to read his Quadruple Objects book to really get a grasp on some key issues), but am instead going to focus on how Levi Bryant puts forth his understanding of an object.

For Levi, the object is essentially split into two parts: a virtual proper being (or substance) and local manifestations. In the forthcoming Democracy of Objects, Levi states:

Because difference engines or substances are not identical to the events or qualities they produce while nonetheless substances, however briefly, endure, the substantial dimension of objects deserves the title of virtual proper being. And because events or qualities occur under particular conditions and a variety of ways, I will refer to events produced by difference engines as local manifestations. Local manifestations are manifestations because they are actualizations that occur in the world. (46)

The object’s qualities are therefore products of the object’s substance, but are not identical to the substance. At the same time, each quality or local manifestation is an actualization of that substance or virtual proper being. Another way of putting this process would be to say that local manifestations cut across the virtual proper being, both actualizing productions of it but also allowing it to withdraw from complete actualization. This is, in fact, one of the main tenants of OOO – that all objects withdraw from both other objects, but also from themselves. But still, regardless of this withdrawal, objects are seen as acts - in that they produce. Here we find Levi's main axiom: there is no difference that does not make a difference. There is no object that does not produce local manifestations, translate other objects, and withdraw from all such relations.

Without getting into the complexities of Levi’s autopoetic and allopoetic systems, we can safely say that this construction of the object is not unlike the process by which desiring-machines operate. Both objects (in Levi’s formulation) and desiring-machines are essentially productive products, and both onticology’s objects and D&G’s desiring-machines produce a realm of potential at every actualization – the virtual proper being and BwO respectively. What D&G’s concepts do, then, when placed up against Levi’s objects is to allow us to better understand how an object can be both limited and open for production. In a lot of ways, the virtual proper being and the BwO act as a structure or limit, while still being a site of production or of recording. I'll be the first to admit that these two theories don't always see eye-to-eye, but when we use D&G to work through these objects, we can broaden the conceptual field of OOO to understand how these objects can be both tablecloths, remote controls, tennis shoes, and stucco while at the same time still be subjects, societies, mobs, and revolutions. Personally, I think D&G can offer us a useful moment of extension from thinking about material things to thinking about all sorts of objects.

Whew! You weren’t kidding, Glen. That was a lot of work. Regardless, I hope I clarified a few things that you had problems with. I’m sorry you dislike OOO, and my own work. And I don’t know if I will change your mind as to the usefulness of OOO, but perhaps that is another project for another post. Instead, my aim here was to show you that these concepts are not all that different.

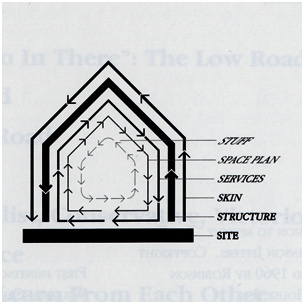

In How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built, inventor/designer Stewart Brand argues that buildings and architecture must be thought of in terms of time and not simply in terms of space. For Brand, buildings consist of six layers, each with its own temporal lifespan:

In How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built, inventor/designer Stewart Brand argues that buildings and architecture must be thought of in terms of time and not simply in terms of space. For Brand, buildings consist of six layers, each with its own temporal lifespan: